Multiple Identities: Intersectional Challenges in the Legal Profession

Columns

- Bloomberg Big Law Business: Life as a "4L"—Lesbian, Latina, Lady, Lawyer—and the Complexity of Identity by Laura Maechtlen, Partner at Seyfarth Shaw

- Above the Law: Moving from a values to value proposition by Bendita Cynthia Malakia

- Lawyerist: Women In The Law Podcast: "Multiple Identities"

- Hire an Esquire: Sparking A Flame For Future Minority Attorneys by Sejal Choksi-Chugh, Executive Director and Baykeeper at San Francisco Baykeeper

Podcast guests

Roundtable guests

Moderators

Transcript

Olympia Duhart: My name is Olympia Duhart, and I'm a professor at Nova Southeastern University's Shepard Broad College of Law. This is LST's mini-series about women in the law. Throughout this series, we've examined the professional and personal difficulties women face in the legal profession. This week, we'll continue the conversation with a special look at challenges women face when they must navigate multiple identities. When a woman lawyer must check multiple boxes—whether based on gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, gender identity or religion—there are additional obstacles she must overcome to succeed in the legal profession. The intersection between social identities offers us the chance to explore the multidimensional nature of bias.

This week, we hear the compelling stories of two attorneys who not only face the challenge of being women in the legal profession, but also confront the complications triggered by an additional layer of diversity that impacts interpersonal and workplace dynamics.

Our first story is about Shawna Surrelle. She's a solo practitioner in Miami, Florida, where she's a litigator. Law, however, is Shawna's second career. Prior to law school, she was a physician. But that's not the only change Shawna has experienced. For ten years, Shawna practiced law in Miami as a man. Today, she lives her life in a new role, making her way as a female attorney. This is her story.

Shawna Surrelle: I started my transition in October of 2014. I kept it pretty much to myself. I didn't start living the role—my correct role I should say as female—until about a year later, recognizing that you can't, I could not go back and forth I was never happy. I transitioned over that year physically, emotionally. And then in October of 2015 I made a bigger leap to pretty much living full time and I have been living full time. I did not go to court, that was the only time I kind of slipped back and it was very uncomfortable, I was very unhappy doing it because I had to let the judges and opposing counsel and other attorneys know, and it was sort of a dilemma as to how do you make that great leap forward.

Olympia Duhart: Shawna was undergoing a personal metamorphosis. But she had the extra stress of being a lawyer and protecting client interests in a world that's still learning to make sense of gender identity. The client piece really adds a complex layer to the equation.

Shawna Surrelle: I wasn't going to like walk into court and say, hey, surprise. It is just not fair; it is not right.

Olympia Duhart: Shawna wanted to tell the judges before appearing before them.

Shawna Surrelle: Of course it is not normal for an attorney to want to just meet with the judge privately in their chambers. So it was always a question of why, what is this about.

Olympia Duhart: So she approached the Judicial Assistants—also known as J.A.'s.

Shawna Surrelle: So I told the Jas and they arranged for a brief 3 to 5 minute appointment with every judge that I called for. And then the JAs would always attend the meetings to make sure there is no mistake of impropriety. I would explain to the judge I am going to start coming to court in a slightly different role. They always asked: you need to be more specific. I had one judge who tried to push me into blurting it out. I said, you know, if you give me a moment I will get to it; but you are going to be sorry and apologize to me for trying to rush me through it. So he kind of he had a very limited amount of time obviously it was supposed to be a brief meeting and I eased into it.

You are talking about going from a what other people perceived as a very masculine short haired older male practitioner and now I am coming in as a visibly happy, potentially slightly younger female practitioner. I took out my camera and my phone showed some pictures of myself, Shawna, and he looked at the pictures for a moment; he looked at me; and he said, "I appreciate you taking the time to meet with me. I am sorry, you are right I shouldn't have tried to rush you." He said, "thank you for not coming to court. I have a really good poker face but this would have definitely thrown me off."

He was fine with it on my first day in court with him, he knew what to expect—he knew I was coming in. My name hadn't been changed yet so he made a big deal out of asking me beforehand how do I address you. He said, "Is just counsellor good enough?" I said that is perfect. And I walked into court, he sat down, kept a great poker face, didn't blink but he did kind of nod and say you know looking good. I said thank you sir, and he moved onto the hearing.

Olympia Duhart: What Shawna really wanted was to be treated like everyone else. And that's what she got.

Shawna Surrelle: I was excited for all the right reasons. I was not expecting any adversity. I already knew that he knew. I already knew that they were going to be supportive. But when I came into court and the bailiff came over and gave me a hug and said you look great, I knew it was a good day. I knew it was easy. The hearing didn't start for another 10 minutes and he kind of just kept repeating wow you look really good. You know it is an ego boost for anybody—for someone who has made a transition, a huge transition like this, a gender transition, it goes beyond ego. It goes to that point of somebody saying it's okay, you look good, you look happy, be yourself, and that is what I was and I have to be honest, the hearing was very smooth. I was very comfortable in the role. I was very comfortable being myself. I was very comfortable with everything. I wasn't treated differently than I had been before.

Olympia Duhart: Of course, everything hasn't been easy for Shawna. One story in particular stands out to her. Not long after she officially changed her name, both legally and with the Florida Bar, an opposing counsel kept sending her emails addressed to her former name and former gender.

Shawna Surrelle: I have showed it to other lawyers and their actual comment was: you should report this. There's nothing to report. It's not a bar violation, it's not an ethical violation, it's just a human violation.

Olympia Duhart: Until this point, things were going pretty well on the name front. But to ensure that nobody thought she was unauthorized to practice law, she did need to change her name with the State Bar in addition to the legal name change.

Shawna Surrelle: I called and the agent at the Florida Bar when I talked to her she was super excited to talk to me, she was equally excited to help me and I was going into court two days later and I said is it, do you think my name will be changed on the bar's website before that hearing? She said I'll do it right now. I said you told me you don't do it for 2 or 3 more days. She said don't worry I'll do it right now. And literally an hour later when you checked the Florida bar website, my bar number is the same. The name's not.

Olympia Duhart: At this point in our conversation, Shawna was smiling. Absolutely beaming.

Shawna Surrelle: It's recognition of who I am, so personally, spiritually, emotionally, professionally it's saying whatever you've done that makes you happy is okay with all of us. Keep doing it, we're good with it, go ahead and do it. To go on the Bar's website people can see my new name that was exciting.

Olympia Duhart: This is not a universal experience for transgender people. Around the same time that the State of Florida granted Shawna's name change, a Superior Court Judge in Georgia rejected a name change petition from a transgender man.

Judge: "The question presented is whether a female has the salutatory right to change her name to a traditionally and obviously male name … The court concludes that she does not have such right."

Olympia Duhart: A recent report by the Human Rights Campaign and the Trans People of Color Coalition documents the harassment, discrimination and violence that transgender people face based solely on their gender identity. In 2016, at least 21 transgender people were murdered due to their gender identity. Seventy percent of transgender people across the country have reported being attacked, harassed or denied access to a bathroom. Others silently suffer through harassment that infects every aspect of their personal and professional lives.

Shawna Surrelle: I will admit that one of my hesitations towards transitioning was always my professional, I need to make a living, this is what I do. So it was always what am I going to do? How am I going to do this? How can I show them court in a dress? How can I face an appellate bench? How can I face a judge? How can I face other attorneys? Can I do this? Can I do this? And this was a dilemma for a while.

Is this really the kind of anxiety or difficulties or complications I want to throw into my life at this point in time? For me there was no question; there was no choice. I waited, I waited, I waited, I waited because I was a doctor. I waited because of family. I waited because I'm a lawyer. I waited because of my friends. And in hindsight I don't know if this would've worked as smoothly any time in my past, but today it's the perfect storm. Everything fell into place in an ideal situation.

Olympia Duhart: Fortunately for Shawna, she didn't have any problems with clients. She was always selective with them—focused on the client more than the case, provided, of course, it's a legitimate claim and within the scope of her practice. During her transition, it really was helpful to worry less about her clients' opinions and more about representing them to the best of her ability.

Shawna Surrelle: First off: my clients are all comfortable with the world around us today and they're all progressive and they're okay with it. I had one client who actually was upset with me because I showed up for a hearing in my former role—and she knows me very well, she's known about the transition—she said why is Shawna not here why are you here. And I said to be honest to protect your interest, the judge doesn't know, the opposing counsel doesn't know. I don't want to distract from the important issues that I'm representing you on. And afterward she said don't do that again, you got to let everyone know. I was just starting to let the judges know and she was right. That's when I started contacting the judges because I knew that my name change is coming, I knew that I couldn't, I wasn't going to live as anybody but Shawna. But I've got very lucky as a transgendered woman. A lot of women in my position lose everything, they lose their job, they lose their friends, they lose their family, they lose their, their entire sense of self and they have to rebuild it all from scratch.

Olympia Duhart: But her experiences with colleagues at the courthouse have still been awkward at times. On her first day in court in her new role, dressed to the nines in a dress with heels, Shawna ran into an attorney that knew her, but did not recognize her.

Shawna Surrelle: Then we stepped out and I called his name and he turned around and looked at me and he said I wasn't sure that was you. I said why didn't you say hello, he said I wasn't sure it was you. I said so you're afraid to say hello because you didn't know me or because you did? And he just laughed and said you look great, gave me a hug, and he went to his courtroom and I went to mine. I, honestly, I think the only thing I get from people occasionally is shock because they never, and everybody has said this with the very rare exception, they never anticipated this from me. But now that they see me, they don't just get it, it fits exactly. The person I am now is the person I am, and I am happier now. And it's actually easier to practice now. I actually enjoy it more because I'm happier with who I am, which makes it easier to do my job. The judges have made it easy, the lawyers have made it easy, the clerk has made it easy, the security bailiffs, and no one has complicated my life here in Miami by giving me crossed eyes in the middle of an oral argument.

Olympia Duhart: Shawna has some advice that's pretty universal.

Shawna Surrelle: If you meet somebody who is transgendered, female to male, male to female, you have to understand or try to understand, please, that looking at them, whether it's staring, whether it's scowling, whether it's smiling, whatever you do, you don't know what's going on in their head and you don't know what they're going through. What they've given up, what they've lost. I've gained more doing this that I've lost but that's not the rule. These girls, and these men also, there's a lot of suffering in some of their lives. If you can really just take a minute out of your day to not be nasty or more importantly to be truly human and acknowledge that this person has done something that is so complicated and so difficult .. it's really an important thing.

If you can just be a human for a minute, it makes such a difference, you can't imagine. Having a judge say you look good, that's enough to validate me.

You know, I may not be the most successful lawyer, I may not win every time, I try as hard as I can. But when it came to this, this is about the most successful thing I've done in my life.

Kyle McEntee: We've kept up with Shawna since we first interviewed her in June. While she was encouraged about her initial treatment back then, her new normal involves more prejudice.

Fortunately, Shawna is both committed and resilient. She is surrounded by supportive people, and she remains unfazed.

Olympia Duhart: During the second half of the show, we'll hear from another female attorney who must manage multiple identities. She's litigator at a large D.C. firm and is one of the millions of Muslims in the United States. Even in a city as diverse as our nation's capital, Islamophobia affects her on a daily basis, especially in today's very charged climate.

John Marshall Law School: This week's episodes are sponsored by John Marshall Law School in Chicago. The school welcomes its new dean, Darby Dickerson, who will lead a diverse student body, faculty, staff, and alumni base. Founded in 1899, the school is known for practical legal training, innovation, and a wide array of graduate programs.

Fatema Merchant: My name is Fatema Merchant, I'm a senior associate at the Washington D.C office of Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton. I grew up in Irving, Texas and as a child of immigrants. My parents are both of Indian origin, they immigrated to the U.S in the late 1960s, My dad has an LLB from Pakistan. He never practiced law but I think he always wanted one of his children to practice law. This is so cheesy, but when I was in the third grade I participated in this mock trial where I was the plaintiffs' lawyer for a little girl. This was a whole scenario where the little girl was a soccer player and she moved with her a family to a school where there was no girls' soccer team. She wanted to be on the boys' soccer team, so I was her lawyer in that little mock trial with all the third graders.

Olympia Duhart: Fatema ended up in law school, but she went in a different direction with her practice.

Fatema Merchant: My practice focuses on regulatory compliance counselling and also internal and government investigation. So, helping companies comply with the regulations and then doing investigations if something goes wrong.

Olympia Duhart: She travels frequently to client trainings and witness interviews. The airplane environment remains a challenge for many Muslims in the United States.

Fatema Merchant: A couple of months ago I was travelling and I was nursing at the time. Traveling and pumping sucks as it is. And on top of that, I just thought to myself, great, I'm a Muslim women in a Hijab with a breastpump that makes loud noises. Every time I went to an airplane bathroom I'd announce to the flight attendants, just to make sure everyone was comfortable, I'm going to go to the bathroom and I'm going to be there for 20 minutes, and you're going to hear the noises out of this machine, and I'm going to come out with a bag full of liquids.

Olympia Duhart: Fatema chose to start wearing her hijab in high school in Texas.

Fatema Merchant: I wear a style of hijab that's called a ridawhich is specific to my small Shia, predominantly Indian community. So it's this long skirt and this cape with a scarf incorporated into it. I started wearing it when I was 16. For me really it was a combination of me wanting to be connected to my community, so for me it's very much about cultural identity, and also a source of empowerment.

My style of hijab is really different. I'm not wearing a head scarf with a Chanel suit, right? This is its own kind of outfit. So the ones I wear, even though I know I'm never going to look like everyone else, I try to keep them to work tones. But the ones that women wear to my mosque are really really brightly colored, very festive, a lot of embroidery.

Olympia Duhart: Muslim women choose to wear the hijab for a variety of reasons.

Fatema Merchant: I think the tough thing for a lot of women who do choose to wear hijab and that's so much a part of their identity is this broad brush of why we choose to wear it, what that means, some very much wear it for religious observation, some for modesty, some for cultural affinity, cultural identity, political views. There's a whole complicated list of reasons why someone might choose to wear it. For me personally, it really helped me develop as a person and keep me grounded to my community, my background. My parents worked really hard to make sure that in coming to America to make a better life for their family still made sure that we understood our traditions, we understood our cultural backgrounds and we honored and felt good about upholding those traditions.

Olympia Duhart: One of Fatema's experiences during law school highlights an ever-present push and pull over how she presents herself.

Fatema Merchant: I remember when I was in law school, we had mock appellate hearings and our professor in preparation for these oral arguments told everyone that make sure you're in a suit and that the women are dressed in professional attire, blah, blah, blah. So after class I felt like maybe I should go tell him that this is just what I wear.

And there had been a couple of months before that, I had gone straight to class from Eid prayer, so I had this super shiny rida on. And so when I went to go tell him this is what I wear so this is what I'm going to wear to the argument he was like yeah, as long as it's not that purple one.

For me that was totally fine, and I understood where he was coming from, but it all goes back to that same idea of how are we going to conform to this idea of what is considered professional, and how do I conform to that when it's so out of the norm.

Olympia Duhart: Her outward display of culture and religion has some obvious ramifications in terms of treatment from others. But what may not be so obvious is what's going through her mind when she takes on any given day.

Fatema Merchant: I think the most significant impact of wearing hijab, of being a Muslim woman, for me might not necessarily be how people react to me but how that plays into my choices of how I interact with the world. So for me, I'm like, I need to be the most loveable Muslim in the world and always smile and look non-threatening and always leave generous tips and don't be the angry brown girl.

Olympia Duhart: How she's treated has definitely changed since she was a child.

Fatema Merchant: So growing up I don't think people necessarily associated me with Islam or thought of me as Muslim. The first question that I remember getting about my ethnicity, really was after the Gulf War, in elementary school was when kids started asking me if I was Iraqi. That was a first time as a child where I really felt that I was different. But what really changed is after 9/11. After 9/11, for me and my family and my community, I mean there was a period of time where women who did choose to wear a hijab were legitimately afraid of being in public.

Like there's an ugliness right now that is palpable. And the hostility is definitely different than even after 9/11. I feel a lot of anger at me and people who look like me that represent an Islamic identity than what I felt fifteen years ago after 9/11.

Right now for the American-Muslim community and especially those that are visibly identifiable as Muslim, for anyone who has a negative view of Islam: like there I am, a visual reminder of something that they dislike, so that in and of itself is going to affect how they interact with me.

I think that having this in the back of my mind is something that I have to deal with in making sure that I still project confidence, I still project power and competence as a lawyer. Those small slights or small experiences can get to you, but at the end of the day it takes a lot more energy to make sure that those things don't affect my confidence and how secure I feel in who I am as a woman, as a lawyer, as a Muslim, as a mom. It's an extra expenditure of energy where, for some, all they have to concentrate on is being a good lawyer.

Olympia Duhart: Fatema's internal struggle and external perception create a feedback loop.

Fatema Merchant: When people look at me they're not going to think, yeah, that's a senior associate at a big law firm. But for me overcoming that initial perception is a little bit of a hurdle. And then once they get to know me, and understand the type of work I do, then we're fine. But there's always that bag of assumptions that people have when they see a Muslim woman in a hijab.

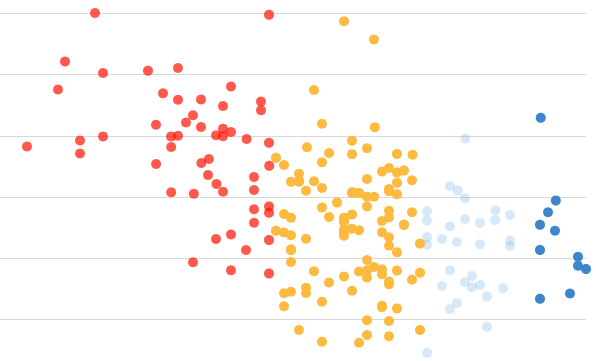

Big Law specifically and I think the legal profession generally is such a relationship-driven industry. If you look at the current power structure, it's still dominated by white men. And it's unlikely that a white man in his 60s is going to look at me and think that you really remind me of myself when I was your age. I don't look like anyone's daughter. So it might not be explicit bias against me but it will be a preference for someone who looks like them. In the short-term that might not affect me as much but over the course of a year those small preferences are going to add up to whether a person makes partner or gets squeezed out of the firm.

The partner I work with who is one of my biggest mentors is a 6 foot 2 self-proclaimed atheist. I'm a petite Indian Muslim woman. And to be very honest it was hard. It's work to forge those connections and to forge a relationship and people don't want to do that work on top of their work. But if they don't put in that work things are not going to change. If I were only looking toward Muslim lawyers as mentors, I would have no mentors.

Olympia Duhart: So what can an organization do to help make diverse attorneys feel more included?

Fatema Merchant: The first step is for a firm to understand, admit that you have a problem. And I think that there's a lot firm leadership and management can do to help encourage partners and people in senior position to help and mentor young diverse associates. I talk with partners about this all the time because a lot of them come from an era where even if they're well-meaning it's an era where you can't talk about race and you can't talk about religion. And that has to change because the only way you're actually going to build closeness, trust, is if you talk about the things that are important to people. And this is very important to young diverse lawyers. So if you stay away from those topics, those relationships will never be built.

Olympia Duhart: Fatema looks to recent societal milestones for a glimmer of hope—a path for a more accepting country for Muslims.

Fatema Merchant: I might be the only Muslim a lot of people know. Probably the only Muslim woman in a hijab they know. Their frame of reference for Islam is me—that's it. If we're really talking about how do we understand each other and how do we move past the dangerous racist rhetoric, it's because you work with people that are not like you. You might have a negative view of Islam but, if I'm right in front of you and if it's a person it's harder for you to make judgements of groups of people if you know someone. There's all those statistics about if a person knew somebody from the LGBTQ community they're twice as likely to support gay marriage because if it's a person in your face that you know and care about, that's going to change how you think about that ethnicity, that race, that gender.

Olympia Duhart: But while society progresses, Fatema still has a job to do. She still wants to make a living. But other people's implicit biases often make that more difficult.

Fatema Merchant: There are people all along the political spectrum that may view the hijab as a form of oppression and may think that it's not truly a choice. That's where the issue lies. If a person wants to respect other people's beliefs but does not truly think that this is a woman's choice, it is going to affect how they view that person's abilities, that person's intellect, that person's power, that person's ability to make decisions and exercise judgement. All of those things could be affected by this perception that she is succumbing to patriarchal pressure.

Olympia Duhart: Fatema says it's exhausting at times, but also a great opportunity.

Fatema Merchant: I was talking to my husband the other day and I was talking to him about how people don't think when they look at me that I'm a Big Law lawyer and he was like yeah, honey but once they meet you, they'll never forget you. And I get that. I get that, for me, assuming I'm good at my job (which I am) it can be an opportunity to present something that's of value.

Olympia Duhart: Like all sorts of attorneys in all sorts of ways, she brings value to the firm beyond consistent, high-quality work.

Fatema Merchant: I think that a lot of people think of diversity as this values proposition, right? Embracing diversity, does this comport with who we are? But if you really think about it, diversity is not just a values proposition, it's a value proposition. The fabric of our country is changing and I think companies realize that their consumers are changing.

Olympia Duhart: Whether it's consumers of products or services, U.S demographics are changing. And with globalization, companies in the United States continue to look outside of the country for new consumers.

Fatema Merchant: With my practice area more and more companies understand and forward-looking companies understand that if you want to be successful you're going to have to concentrate on the 95% of the world that is in the United States. Professional counsellors that understand other cultures is a benefit and not a penalty, but at the same time it goes back to this idea of what do you think of when you think of a successful partner at a Big Law firm or associate at a Big Law firm.

Olympia Duhart: Despite the challenges, Fatema wants to make partner at her firm.

Fatema Merchant: Part of it to be frank is so I can be a Muslim woman partner in a hijab, even though that's not how I want my professional identity to be defined, I want to be a skilled and thoughtful practitioner who happens to be a Muslim and happens to be a woman and happens to be wearing hijab and happens to be a mom. But at the same time, I think being a partner and part of the leadership of this firm is not only a powerful statement to the firm, but to the broader legal community and to the broader world about the value of American Muslim women in the professional sphere.

Olympia Duhart: Thanks for tuning in. Stick around and listen to the roundtable discussion we held at The John Marshall Law School in Chicago about the privileges and challenges of multiple identities. I'm Olympia Duhart. This episode was produced by Kyle McEntee. Music by Brad Kemp. Thank you to all of our guests and to Kimber Russell, Marissa Olsson, Ashley Milne-Tyte, Carin Ulrich Stacey, and Susan Poser for your help. We also want to thank Diversity Lab and Debby Merritt for a generous donation very early in the project. Next week, we look at some solutions to the problems identified during our mini-series.

Women In The Law is a production of Law School Transparency. To learn more about LST, visit LawSchoolTransparency.com. To learn more about this mini-series, visit LSTRadio.com/women.

Explore episodes

Hey Sweetie!

Sexism in the legal workplace

In the Media

How women lawyers are portrayed on TV and in the news

Leaky Pipeline #1

Examining the premise of a leaky pipeline

Leaky Pipeline #2

From hiring to retention to leadership

Multiple Identities

Intersectional challenges in the legal profession

Solutions

Rules, sanctions, and awareness

Search

Listen on

Distribution partners

In addition to traditional podcast channels, the series will enjoy wide distribution through a growing number of partners. Each partner will publish at least one article per theme. Across a wide variety of networks we will foster a lively discussion over the show's eight-week run.

We hope to empower both women and men to recognize and constructively address a wide range of workplace issues that negatively impact women, the organizations and firms they work for, the clients they represent, and the society we all live in.